STOP! Or at least slow down! Do your disk brakes have as much power as a wet biscuit? Are your brake levers as effective as a wooden frying pan? Do you need to brake with all four fingers? Follow our tips to maximise your brakes and feel G-forces that will make your eyes bulge.

Remember the first time you tested your new bike? Chances are you looked to your riding buddies and went ‘woah, these brakes are awesome’. But just like that cutting-edge laptop you bought last year, slowly but surely the performance dwindles, leaving you panic braking into corners and swearing at the spinning ‘loading’ icon on Netflix. The easiest way of improving the performance of your brakes is to simply buy new ones, and the best resource for that is our 2018 disc brake group test. However, we don’t all have a bank balance with lots of black 00’s so we show you how to make the most of your current braking setup.

Size matters. Your rotors are too small!

Why is it when it comes to rotor size, convention tells us to use 160 mm for XC, 180 mm for Trail and 200 mm for DH? We call ‘bullshit’ on that advice. Why should we not have more powerful, controllable and reliable braking in all categories? Moving up from a 180 to 200 mm rotor adds just 40g (SRAM CENTERLINE) to the bikes weight, about the same as a small multitool in your pocket, but improves the braking torque between 20 and 30 % – a monstrous improvement. Fitting a bigger rotor will not only give you increased power, reduce arm pump, but also improve modulation and heat management as the rotor will heat up slower and cool faster over the larger radius. Our top tip would be to run 200 / 200 mm rotors for all applications, ultimate force, we would even consider a 220 mm on the front for 29ers. Before increasing rotor size check the recommended maximum rotor size for your frame and fork.

Tip tap for a better bleed.

No matter what disc brakes you have fitted to your bike (OK, maybe not if you have cable brakes, but then you really should upgrade), they all work in the same way – a piston in the lever pushes fluid down through the hose and forces paired pistons in the calliper to squeeze the pads against the rotor. Brake fluid, whether it be mineral oil or DOT fluid, cannot be compressed, meaning all the force you put in at the lever is delivered to the rotor. However, if over time that fluid becomes contaminated with air past the seals, air can compress and when you pull the lever it compresses the air rather than pushing the pads against the rotor. If your brakes feel spongy at the lever it’s time for a bleed. There are many excellent online resources available explaining how to bleed your brakes, but here’s a pro tip from us. When bleeding, always give the calliper a couple of firm taps on the body (we used a plastic-wrapped Allen key handle), this will dislodge any air tenaciously hanging on around the pistons and give a much better bleed. Also, flick the hoses and tap the brake lever body, air is your enemy when bleeding brakes, do not let any survive.

Don’t be a doughnut, bed your brakes in properly.

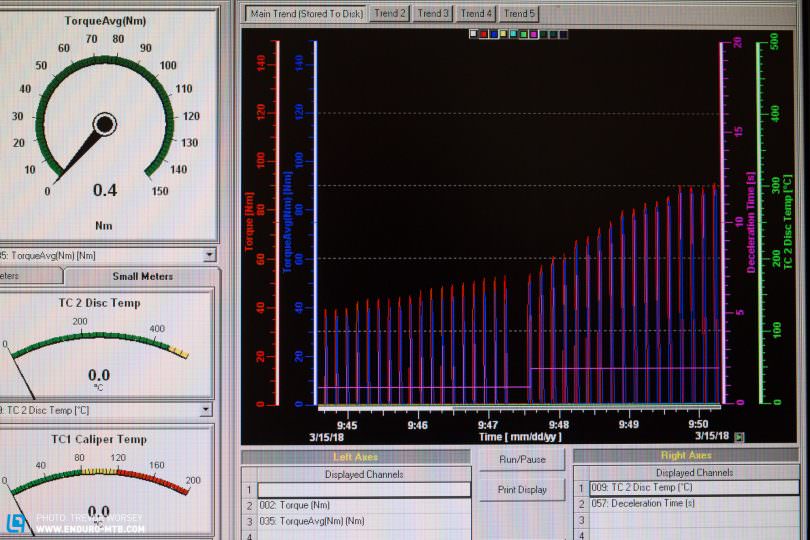

‘Bedding in’ is the process where the disc brake pad transfers some of its material on to the rotor, filling in the microscopic imperfections and ensuring maximum friction for the life of the brake pad. This is also the process that everyone gets wrong. We live in an immediate world, we expect instant results, but simply throwing in some fresh pads, doing a couple of stoppies and then hitting the trails for some violent braking to bed them in simply won’t work. All you do is build up heavy deposits on the sections of the disc where you locked the wheel, resulting in imperfections, noise and sub-optimal braking – error. Brake pads are expensive, and it’s essential to spend five minutes bedding in your pads properly to the rotors. Find a long, gradual hill that you can roll down comfortably. Once up to a gentle running speed carefully apply a single brake smoothly and firmly, you don’t want to skid or stop, just controlled braking. Just before you reach a standstill release the brake and allow the bike to return to speed, no skids or stoppies, then repeat. Do as many repetitions as you can, or until the brake no longer feels like it is improving. In the lab, we observed that at least 10-20 repetitions were needed to reach maximum braking torque. If you are short on time you can wet the pads which will help them deposit faster.

Lever setup, get your controls dialled in

Have a good look at your brake setup on the bars, how does it look? An optimized cockpit will reduce arm pump, improve brake performance and increase confidence – all good things, and it only takes five minutes to set up. Most brakes give you control over the position of the levers on the bar, the angle of the lever and the reach. When setting up the position on the bar, you should move the levers so the braking finger rests on the crook at the end of the lever in a straight line with hands and lower arm, too far inboard or out will reduce your efficiency. The angle of the brake levers is largely down to personal preference and still contested, but generally active riders who love steep and gnarly terrain may prefer a flatter lever position for more power and to suit a lower, more aggressive position, while touring focused riders may prefer a more comfortable in-line position with your wrist and forearms in line with the braking finger. If your brake has a reach adjustment, we recommend winding in, or out, the adjuster until the lever blade fits in line with the first finger joint, or in the middle of your finger if you are a skilled rider looking for maximum late-brake power.

Sintered vs Organic, not all brake pads are created equally

The material used in your brake pad has the biggest impact on braking performance, fade and longevity. Manufacturers invest a small fortune testing and improving pad material, but most fall into two types, organic and sintered. Organic pads consist of fibres of rubber, carbon or kevlar bonded together with resin, while Sintered pads consist of metal particles fused together under great pressure. Softer organic pads normally bite harder, and run quieter, in our tests comparing one manufacturer’s sintered and organic pads, braking torque was up around 10%, and deceleration times were improved around 9%. However, organic pads perform a lot poorer on long alpine descents as the resin boils with the heat causing fade and wear very fast in the wet. Sintered pads handle heat a lot better than organic pads, and work more consistently in the wet – but they are noisy. Don’t forget aftermarket pads too, in our tests fitting the Trickstuff Power+ brake pads to the SRAM Code R resulted in a 20% improvement in average braking torque, and an average of 18% improvement in deceleration times, they were silent too. If you ride a lot in the alps or in the wet, sintered may be the pad for you, if you like power and silence, then organics may suit better. Pro tip, a lot of the ENDURO team run an organic pad in the front and a sintered in the rear for the balance of power and longevity. Some manufacturers recommend changing the rotor if swapping from sintered to organic pads, make sure you check your user manual.

Centralise the calipers

When you brake, the pistons in the calliper move out to push the pads against the disc. If the calliper is not directly aligned above the rotor, the piston or pistons on one side will have to push further out to contact the disc, reducing efficiency. Look at your pistons, if one side is much further out than the other, your calliper is misaligned. Time to get dirty, drop the wheel out of the frame or forks and remove the pads, with a tyre lever, or another suitable device gently push all the pistons back into the calliper, resetting it. Re-insert the pads and wheel. Loosen the two main calliper bolts (attaching the calliper to the frame or fork) just enough to allow movement. Hold the calliper centrally over the disc rotor with an even gap each side and carefully tighten up the calliper bolts. Pump the brake lever a few times to allow the pistons to extend out evenly and the brake rotor should now sit centrally within the pads. To fine tune, undo the calliper bolts just enough to allow movement then pull and hold the brake lever hard, this will move then lock the calliper into position, keep the lever held in and tighten the bolts. This should result in drag-free riding.

Enjoy your next ride!

Did you enjoy this article? If so, we would be stoked if you decide to support us with a monthly contribution. By becoming a supporter of ENDURO, you will help secure a sustainable future for high-quality mountain bike journalism. Click here to learn more.

Words & Photos: