Steel is real, but does that make titanium even realer? In this article, we’ll find out what these two exotic materials are all about and what’s behind them. What are the differences in terms of manufacturing, finishing, and trail performance?

The mountain bike bubble can sometimes feel like an inverted world. For example, just look at the materials used: steel is ubiquitous in everyday life, including houses, cars, trains and much more, whereas carbon is a rare high-tech material. For many mountain bikers, however, carbon is commonplace, while steel bikes, on the other hand, are rather rare, often exclusive custom-made bikes. However, titanium bikes are rarer still – most people will have heard of this material mentioned in connection with expensive watches, jewellery, or surgical implants. We took a closer look at steel and titanium as a frame material, exploring the differences, what sets two materials apart, and how they were used for mountain bike frames in the past. Of course, we also tested two identical enduro hardtails – one made of steel and one made of titanium – comparing them head-to-head on the trail.

Steel vs titanium – General differences

Steel isn’t a chemical element – in other words, it’s not a pure substance. Instead, steel is composed of several elements. The primary component is iron, which is combined with proportions of up to 20% of other elements, such as nickel, chromium, or molybdenum. Along with small amounts of less than 1% of aluminium, niobium, vanadium, or titanium. This mixture is called an alloy. What is added in what proportions depends very much on the intended use, as the properties of the material can vary greatly as a result. The stiffness, strength, and corrosion resistance of the steel is influenced significantly by the alloy used, and it’s a science in itself.

Titanium, on the other hand, is a pure element that it can’t be broken down into other elements by chemical means. With a density of 4.5 kg/l, it is still considered a light metal – metals that are lighter than 5 kg/l. As such, titanium is much heavier than aluminium, which has a density of just 2.7 kg/l, but much lighter than steel, which comes in at around 7.8 kg/l, depending on the alloy. However, the strength of titanium is almost the same as that of steel. Similar to aluminium, titanium frame tubing never consists of pure titanium. Instead, it’s also an alloy containing further elements of aluminium or vanadium. However, the extraction and processing of titanium is significantly more complex than that of iron or steel, which makes it several times more expensive.

A quick look at the origin story of mountain biking

The first mountain bikes weren’t actually made to go off-road. Instead, riders in the 70s simply resorted to converting their steel beach cruisers, called clunkers. The bikes were heavy and sturdy, making them ideal for blasting down the gravel roads of California’s mountains. It wasn’t until a few years later that a small group of frame builders started making bikes that were specifically intended as mountain bikes – and it’s the first time they were actually called that. However, they looked and rode very much like the beach cruisers of before.

The first mass-produced mountain bike was the Specialized Stumpjumper, launched in 1981: it had no suspension, generally had little in common with today’s mountain bikes, and it was made of steel, of course. At that time, aluminium was still considered a high-tech material, mainly used in the aerospace industry. It wasn’t until the end of the 80s that Cannondale launched the first mass-produced aluminium bike. Following that, aluminium established itself as the standard frame material due to the advantages it offers over steel. Aluminium has a relatively low melting point, is easy to process, and can also be cold-formed.

Many years later, in the 2010s, the first carbon bikes appeared. Carbon, on the other hand, is a composite material made of carbon fibres, which are woven into strands or mats, bonded with a resin, and then baked and thereby hardened in a mould. However, the first carbon bikes were about the same weight and less durable than their aluminium counterparts. It was only a few years later that carbon technology had become advanced enough to produce lightweight and, above all, strong carbon frames.

Nowadays, a bicycle industry without carbon is unthinkable, including everything from city commuters, to road bikes, and MTBs. Now, almost all new bikes in the performance segment are made of carbon, as it gives designers more freedom in realising different frame shapes. In addition, the developers can adjust the properties of the frames by changing the carbon layout, adding flex and stiffness where required.

Steel, on the other hand, has almost gone extinct as a MTB frame material. However, the material remains popular amongst a small group of purists and individualists – they praise the material’s simplicity, but also its flex, which promises a comfortable, forgiving ride.

But what about titanium? Because of the high price and elaborate processing, it’s never been widely used. Across all bike categories, it has always been a material reserved for connoisseurs who have a big enough budget.

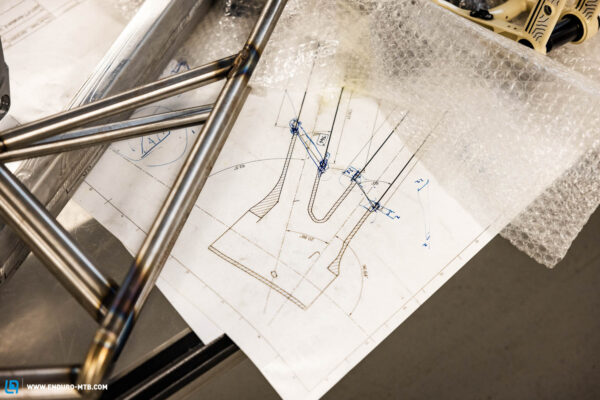

Our test bikes – The Stanton Switch9er GET FAST models

Stanton are a small brand from Derbyshire in the UK – the country that stands as the undisputed stronghold of steel bikes. They manufacture mountain bikes exclusively from titanium and steel – from hardtails to full-sussers, although for some time now they have no longer been made on the British isles, but in Asia. After Stanton UK recently went into administration, 1bike4life stepped in, a Munich-based company that is dedicated to selling bikes that will stay with you for life. They took over the factory’s already produced stock and at the same time registered the rights to the name in European countries as well as various third countries such as Switzerland, Japan or the USA. There, the distribution is now implemented by 1bike4life. With their three drop bar brands Rennstahl, Parapera and Falkenjagd, they already have plenty of experience with noble bikes and exotic frame materials. Falkenjagd exclusively produces titanium frames, while Rennstahl – who would have thought – relies solely on steel. With Stanton, a brand for MTB use now complements the portfolio of the Munich-based company.

The steel Switch9er has been in Stanton’s line-up for many years and has remained unchanged for a long time – never change a running system, as they say. In addition, they now have a titanium version, which has the exact same geometry. The only differences besides the price are that the cable routing of the Switch9er Titanium is internal and the frame is only available in a classic raw finish, retaining that unique titanium look. The two hardtails are perfect for testing the characteristics of the two materials, as there is no rear suspension, shock tuning, or other variable that could affect the ride feel and falsify the results. We tested the GET FAST models, which are absolutely identical apart from the frame material.

Stanton Switch9er in steel and titanium – What are the differences on the trail?

Since both bikes have the same geometry, they feel very similar at first. Both variants have a comfortable and upright riding position that doesn’t put too much weight on your hands. Thanks to the rigid rear end, every pedal stroke is immediately converted into propulsion, giving the bikes a very lively feel.

You’ll feel the first differences when you stand up to sprint: the titanium version feels a little softer and you can feel a slight bit of flex in the frame when you really put the hammer down.

On the descents, these differences become even more obvious. The Switch9er Ti is noticeably more comfortable and less strenuous to ride, as it shakes you around less in rough terrain. Overall, the titanium version feels a bit more forgiving, as the more flexible rear end tends to snake through demanding sections instead of getting pinged about. Together with the weight savings of just under a kilo, the titanium bike is our firm favourite. You’ll just have to make peace with the raw finish and the internally routed cables – besides being willing to pay the higher price.

For whom is the titanium and for whom the steel model?

Stanton’s steel Switch9er enduro hardtail is for all the nostalgics among us who want a steel bike that’s reminiscent of the good old days of mountain biking. In return, you get a direct ride that converts every watt into propulsion. Of course, you can’t disregard the fact that you’ll also save yourself € 1,300.

The Switch9er Ti, on the other hand, is a bike for the individualists among individualists and those who want an exotic MTB that stands out from the crowd with its premium frame material. In addition, you will be rewarded with a forgiving ride that has few disadvantages, making the ride less strenuous and more comfortable.

Conclusion on steel vs titanium on the Stanton Switch9er

“Steel is real” is a nostalgic movement among mountain bikers who like reminiscing about the origins of the sport by riding steel frames. Titanium is much more exclusive and has a completely different origin. Now, however, the materials share a similar market among purists and connoisseurs. On the trail, the titanium bike offers more comfort and a more forgiving ride. However, due to their more elaborate production and processing, titanium bikes are in a wholly different price segment, too.

For more information, visit 1bike4life.com or stantonbikes.de.

Did you enjoy this article? If so, we would be stoked if you decide to support us with a monthly contribution. By becoming a supporter of ENDURO, you will help secure a sustainable future for high-quality mountain bike journalism. Click here to learn more.

Words: Simon Kohler Photos: Peter Walker