Elite BMC racer Lorraine Truong is locked in a battle with the very real effects of repeated concussions. This is her story.

“The best way I can describe it is like in a motor car… imagine you had a great car with a silent engine, then one day you had a crash. The car still drives OK, but the engine is now noisy, clanking, and howling – that’s how it feels living inside my head.” -Lorraine Truong.

As riders we all live with injuries. Scars trace like memories over our bodies, telling tales of risky lines and poor choices. Most become trophies worn with pride, but occasionally they silently manifest themselves deeper, like a demon in the shadows. For elite BMC racer Lorraine Truong, multiple concussions have left her locked in a personal battle against the debilitating effects of repeated trauma to the brain.

For the 26-year-old BMC factory team racer, everything changed on the 19th of July, 2015. On a stage of the Samoens EWS, she crashed and hit her head hard. No stranger to concussion after suffering many during her career, after being helped off the hill her immediate thoughts were “Can I race next week?” However, something was wrong; her brain was ablaze, and the pain just would not subside. It was not until three days later when, consulting a doctor who had a specialist interest in multiple concussions, alarm bells started ringing. She was broken… she had hurt her brain, and there would be no band-aid fix. The repair would take time and require a change of life with no riding, not much of anything – simply devastating news for a driven athlete.

Understanding of concussions in the medical community is still embryonic, and being a woman used to timelines, structure and progress, it was draining for Lorraine to be cast into a campaign filled with confusion, disappointments, and the unknown. Days became weeks, weeks became months, months became a year… and Lorraine is still trapped in an unfamiliar world, a confusing environment where energy is the currency and even the simplest tasks are costly. Walking, conversation and even sleeping have become mammoth undertakings where, even in a darkened room, her mind continually fizzes and hums with static. For Lorraine, life now has to move at a different pace.

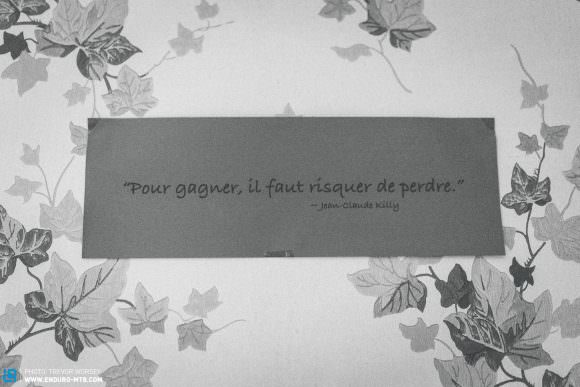

Elite-level racing is by definition a risk. As competition increases, elusive seconds are won by pushing bikes to the very edge of control, meaning crashes are inevitable. In pursuit of short career windows and elusive sponsorship deals, an attitude of ‘toughen up’ and ‘as long as I can still race’ sees more and more racers taking to the startline while still nursing injuries. As a sport, we have grown almost used to pro riders coming and going from the scene, accepting injury as part of the game. Elites light up the podium for one race before disappearing with an injury the next; the media moves onto the next big thing while the forgotten racers struggle on the fringes. But what about concussions? Impacts to the head are dangerously common, but still widely misunderstood.

Very recently, in an excellent piece of journalism, the very real dangers of Post-Concussion Syndrome (PCS) and Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE) were revealed to the riding community, unlocking a Pandora’s box and showing how repeated impacts can be far more devastating than the sum of their parts. While the exact mechanism of concussion is still widely misunderstood, experts are in agreement that with each concussion received, the effects are exponentially more harmful, like pouring petrol onto a smouldering fire. Repeated head traumas cause a structural change within the brain; strands of clumped proteins strangle sensitive neurons, leaving the sufferer with memory loss, depression, confusion, mobility issues, and unrelenting static.

I first met Lorraine two years before the incident while she was practicing for the EWS Scotland. I was immediately struck by her explosive personality; she reminded me of a firework, charged with determination and mischievous fun. Her skills on a bike were a joy to watch – naturally talented, she was always a danger to the top step. A high achiever in every way, Lorraine was born to an academically gifted family. She excelled as an elite athlete while simultaneously working as an engineer for BMC and completing a BSc in Material Sciences and Engineering and an MSc in Mechanical Engineering. However, what really shone was her infectious passion for fun and a silliness charged with a boundless energy that was electric. Now, one year after her accident, I sit inside her 17th-century family home in a sleepy village in Switzerland, the smell of her father’s traditional fondue creeping around the rustic kitchen.

As Lorraine explains how her life looks now, even though her smiles and mischievous spirit light up the room, I feel her crushing frustration at her predicament and see that every minute of concentration is now a drain on limited reserves. Emotion and humour flow effortlessly, but occasionally thoughts get lost on the journey to her mouth, taking a road that is momentarily blocked. After an initial rush to be well again, Lorraine has accepted that the road will now be a long one.

Returning to cycling is still the main (but currently very distant) goal, as even short walks are exhausting, requiring the support of a stick. Inside her head, the normal ambient drone of conversation, cities, and everyday life is a deafening roar of stimulus; bright lights are blinding, and for her even the simplest tasks we take for granted are not always possible.

For athletes, it’s hard to communicate weaknesses, to show vulnerability – especially of the mind. As we drink our fourth cup of tea, Lorraine explains that one of the hardest steps for her was to learn acceptance; to accept that something is wrong, that it does not need to be hidden, and it’s OK to need help. In the beginning, she tried to hide her difficulties – not only to escape her fears, but also to avoid being judged or frighten those around her. The words ‘brain injury’ trigger a fear in people: mental health issues are taboo and uttered in whispers. On the surface, Lorraine’s injury lies hidden from view, and for a long time she pitched herself against it, putting on an act of disguise, bravery, and positivity, forcing achievements before she was ready. Ultimately, the effort consumed all her precious energy, energy which was so vital for recovery. She did not want to hear “You look much better” or “It will make you stronger in the end.” She had been happy with her previous life. She was young and strong and a gifted rider, now disconnected from the world that had been taken from her – it was unfair and it hurt.

Loraine was keen to share her thoughts and penned this emotional addition: “It’s quite hard for me to talk about my feelings, as most of the time I try not to think about them too deeply so that I can keep going. But I guess that the three most important feelings just now are frustration, shame, and sadness.

Frustration, because of how my brain injury limits what I can do and how I must do it. I can be as full of motivation and willingness as you might be, but if my brain is not ready, I will have to give up. Some days, it can mean only being permitted a couple of minutes of activity. Even when I can function, everything is such an effort. Just being in the present and staying focused is a battle. My thoughts, words, and body control are slipping away all the time. It’s so frustrating, as well as exhausting. It makes me want to cry with despair.

Shame, because I am not independent anymore. I need daily help, sometimes for tasks so simple that I wish I could disappear. I know that my caregivers are happy to help me whenever I need it. But facing that I need that help is hard work.

And finally, sadness. Sadness for the person I was and who I am not anymore. Sadness for all the things that gave me joy and that were stolen by the injury. Sadness for the dreams I was living – or touching with my fingertips – and for all that slipped out of my reach in a sudden crash. I have to grieve the person I was before I can welcome who I am now.

It has been a very long and difficult journey to accept that in a couple of days I went from being a world-class athlete to a brain-injured person. And that even if I try very hard – and I did try very hard – I can’t rush the healing process.

For about one year, I thought this injury was like any other. I thought I would be back to where I was before if I believed in it and tried hard enough. But now I realize that in a way it doesn’t depend on me as much. Fighting a brain injury is a lost battle, simply because you actually need your brain to fight. So the only thing I can do is make the most of what my brain can achieve at the present moment and use that power to keep moving forward.

In truth, I am going through very dark times. Moments when I feel too small, too weak, too useless to keep going. When I want to crawl in a ball and evaporate. However, I don’t really have the choice but to move forward. I don’t mean to be crude, but either I commit suicide and make it stop, or I deal with it the best I can. There is no other way.

Even if it is painful, I think I can face my situation better now that I have become more realistic about the injury. I still dream about spending my life riding bikes. But now it’s closer to the dream a five-year-old has to be an astronaut. It may happen, but it may also be equal to wanting to be a superhero. But even if he or she won’t be an astronaut, a five-year-old is still a person that can enjoy the present moment. This is what I am trying to do on a daily basis. Respect my brain for what it can do, such that it allows me little moments of happiness – and nothing beats a good laugh with friends to cheer me up!

In my journey so far, I have had two inspirations. I thought of Jamie Nicoll’s story a lot. He showed that even when you are in a bad state, you can still hold onto the dream of being a pro rider – that it is possible. It was a huge resource of hope and really helped me going through the shock of the first months. Now that I face the reality of my limitations, looking into what Kevin Pearce does helps me. He also had to give up competing after believing he would be back. He had to find a new path for his life, and this is the journey I am starting now.

Being more realistic has made me change my expectations. I now know that simply being able to get out with friends for an hour on bikes or skis would be amazing. Simply to enjoy the feeling of movement and to have fun. I also want to be able to find a way towards a more independent life. Being able to take care of myself at some point seems essential. I also want to find my place in society again, to feel that I belong to this world and that I can contribute to it somehow. I hope I can find a life motivation as powerful as riding my bike used to be. Until then, the biggest challenge I face is being happy and having fun despite being brain-injured. To see all achievements for what they are. Not as a step towards something else, but as a something that makes me happy in itself.

I know that brain injury is a difficult topic to deal with from outside and that most people want to help, but don’t know how. If I am honest, trying to encourage people with brain injuries by saying that they look much better or that they will for sure be able to achieve something is not the best way. They might look fine from the outside, but be constantly struggling inside. Thus, trying to be reassuring might have the opposite effect by making them feel alone and misunderstood. So my advice is to try to imagine how it feels like to suffer with a dysfunctional brain and to give empathic encouragements.

I feel that I really do need encouragement. I need people to show me that I am not forgotten and that I am still somehow part of the biking community. I almost constantly feel that I am not strong enough and that the battle is too hard for me. So I can never hear enough that people are behind me, and that even if I don’t feel like it, I have to keep doing my best. Some of the toughest times are race weeks, and simply sending me a thought – by sending or posting a photo or a video for instance – has a huge impact on my morale and my ability to cope with the situation, filling up the positive tank. Brain injuries are lonely challenges, but you can make me feel loved and cared for.” [Lorraine Truong]

Before the accident, Lorraine functioned at superhuman speed, and now even exceptional progress will always be too slow for her; she is learning to listen to her body and is gently moving forwards, but the road is long. She now finds her motivation in different ways, documenting her elevating achievements and crushing disappointments through inspirational writing on her website, taking pleasure from the little moments that we all take for granted, laughing with friends, walking her dog, or the release brought by the good days.

But there is, of course, hope. Courage and youth burn brightly behind her eyes, and even though the darker days may leave her defeated, her fierce resolve pulls her back. Lorraine’s recovery is now measured not in training timescales or physio, but in patience, uncertainty, and trust. It’s not a battle she chose or wanted, but she is a fighter and will fight it all the same. While I wish more than anything to say that she will be ‘back in no time,’ I do not wish to disrespect the difficult journey she has ahead. However, after seeing that spark in her eyes, I am left in no doubt that she will reach her goals.

While Lorraine’s journey is a personal one, as a community we can help support her and learn from her experience. The mountain bike community is still ignorant to the very real dangers of multiple concussions, and it’s time to raise awareness of the risks that we unknowingly expose ourselves too. We need to spread the message that it’s NOT OK to ride when our brains are recovering, that rest and recovery should be equally as important as competition and possible reward. Never let your friends risk their health after taking a big crash, and seek help if you are worried after suffering a concussion yourself. Only by learning from brave riders like Lorraine will we be able to do more to protect what is most important.

You can follow Lorraine’s progress on her website and Instagram at @lorrainetruong and follow the #mybrainmyrules tag, where her honest accounts show the reality of dealing with a brain injury through the eyes of someone who is living with the noise. Sometimes all you need is to know that there are people on your side, so let’s give her our support.

We can help

If this story has moved you and you want to help Lorraine, well you can! Lorraine is hoping to travel to the USA, where revolutionary new brain injury techniques are being pioneered, offering a very real chance of success. Lorraine has set up a fund me page for those who want to help support her on her difficult journey. It’s time for the riding community to rally in support of one of our own. We hope you will want to help by donating to Lorraine Truongs Fund Me page. With our help there is more hope.

Did you enjoy this article? If so, we would be stoked if you decide to support us with a monthly contribution. By becoming a supporter of ENDURO, you will help secure a sustainable future for high-quality mountain bike journalism. Click here to learn more.

Words & Photos: