What’s going on in the enduro scene? After a frustrating EDR racing season, factory teams are throwing in the towel, resulting in several pros ending up on the streets. The heavy atmosphere hanging over the sport is accompanied by rumours that the EDR will soon be coming to an end, at least as we know it. We spoke to team managers, racers and organisers to understand what’s really going on, and to find out whether enduro racing has had its day.

Let’s face it: enduro racing is having the toughest time since its inception. Bike brands are pulling their support for race teams, and according to persistent rumours in the scene, there will be no more EDR in just a few years, with the focus shifting gradually towards ebike racing. But what are the reasons for these changes, and why has the best sport in the world turned into a nightmare for some?

Professional enduro racing has changed fast! Epic days of racing in exotic, unknown mountain resorts have given way to multi-stage downhill races in bike parks, while lone team mechanics in small Ikea gazebos have partly been replaced by full factory support teams in huge trucks. In other words, enduro racing has evolved and become more professional. While at first glance, this isn’t at all a bad thing, for many of us it has turned the once unique, rad enduro racing spirit into mere frustration.

Unfortunately, with the rapid professionalisation and commercialisation of our sport also comes a bitter setback: several factory teams are pulling out of the series, with countless top riders ending up on the streets and struggling to find new sponsorship contracts, given the declining state of our industry at the moment. And that’s not to mention the persistent rumour that the Enduro World Cup is on the brink of collapse.

Here at ENDURO magazine, we have increasingly withdrawn from the racing scene, yet we struggle to understand why there is so little conversation about the current state of professional enduro racing, or at least reporting about the persistent rumours and the EDR’s questionable future. That’s why we feel obliged to break our long silence about enduro racing and speak out again. We’re not here to pick on those who have worked hard to bring enduro racing to success during our media absence, but to raise awareness among readers and provide the industry with positive, constructive feedback, providing some well-needed food for thought. Because something needs to change before it’s too late and our beloved sport comes to an end.

In order to get the full picture of the different perspectives on the situation, and maybe glean a glimpse into the future of enduro racing, we spent countless hours on the phone, met with insiders, had some long email exchanges, and interviewed over 900 ENDURO readers from all over the world.

From enduro superstar Jack Moir, who secured the overall title in the 2021 EWS season, to local hero Max Pfeil, who takes time off from his day job to jet around the globe and has already achieved impressive EDR results. We also chatted to industry insider and photographer Sven Martin – having covered every single race since the very beginning back in 2013, Sven has become part of the furniture at the EWS, and has some deep insights into the scene. And it’s the same for enduro veteran Jerome Clementz, who won the very first EWS season, and has gone on to found his own racing series in France. We also spent a couple of hours speaking with Robin Wallner, manager and racer at the IBIS Factory team, as many of his teammates are now jobless following his team’s withdrawal from the series. German racer Ines Thoma has been part of the EWS from the very beginning and competed rather successfully in several E-EDR races last season. We also chatted to Claus Fleischer, CEO of Bosch eBike Systems, while visiting their headquarters. We found out more about the development of e-racing, possible new formats and the influence of the sport on young people.

Needless to say, we also contacted the founder of the EWS, and now Vice President of Cycling Events at Warner Bros. Discovery Sports, Chris Ball as well as Kate Ball, Head of Communications at the UCI Mountain Bike World Series. Despite exchanging countless emails, they weren’t able (or didn’t want?) to answer our questions concerning the matter, neither denying nor confirming that the EDR will carry on after 2025. In addition to this, over 900 readers took part in our digital survey, sharing their opinions on the current state of the EDR and telling us how they feel about its future.

The birth of the Enduro World Series and the transition to the Enduro World Cup

To help us better understand the matter, we’ll have to start from the very beginning. Let’s rewind back to the “olden days”, those which many of us will remember fondly. It’s the end of 2012, and Chris Ball unceremoniously quits his job as a UCI commissioner to found the Enduro World Series. The EWS received support from the Enduro Mountain Bike Association – EMBA – which Chris was actively part of, together with Enrico Guala and Fred Glo, founders of the Italian SuperEnduro PRO series and French Enduro series, respectively. Crankworx Event Manager Darren Kinnaird was part of the team too. EMBA represented the interests of riders and was also backed by the industry, with big companies like Santa Cruz, SRAM and FOX, as well as professional racers like Tracy Moseley and Jerome Clementz, allowing it to actively contribute to the development of our sport. Over the years, EMBA evolved into ESO – Enduro Sports Organisation – which should be familiar to most active racers.

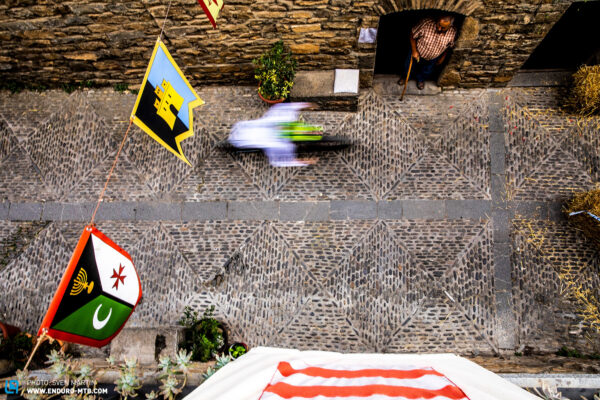

The very first season of the EWS kicked off in 2013 in Punta Ala, Tuscany and was a combination of many individual races, spanning two continents. In the first year, for example, the EWS headed to the USA, and the Crankworx Festival in Whistler. In 2014, in addition to the classics such as Finale Ligure and Whistler, there was also a race in Chile. The adventurous nature of the races and fascinating locations gave the EWS its special, legendary flair, which helped it grow into a global event. Every year, new, crazy stops were added to the event list, including places very few people had been before.

We at ENDURO also threw ourselves headfirst into enduro racing, and the EWS played a key role in the foundation of our magazine. Back then, we released a comparison test with the best EWS race bikes of 2014, which was produced together with Ruben, who went on to found RAAW – and the support of Enrico Guala in Finale Ligure. Those who have followed us from day one, might remember when former editor Trev stepped in for Jerome Clementz in the Cannondale Factory Team, forming part of a professional EWS team for a weekend. Of course, we produced plenty of race content including results, overall standings and photo highlights, and even if you won’t find such content in our magazine now, we’ve never lost sight of the sport.

While enduro racing was still somewhat ridiculed at the time, especially by young pros, and seen as the last step before retirement, other professional riders from different disciplines and even mountain biking stars like Steve Peat, Greg Minnaar and Nino Schurter, gathered to compete against each other in the EWS. The EWS has merged many MTB disciplines and brought athletes closer together. The refreshing versatility of enduro, and the unique atmosphere at the multi-day long events sparked interest and ensured steadily increasing popularity, allowing the EWS to quickly lose its “retirement home” status.

Inevitably, the sport’s growing popularity caused a stir in the industry, with the enduro spirit flowing through its many different layers, and bike manufacturers embracing the new concept. Support was increasingly strong, both for the riders and teams. There was more publicity and the rules became increasingly strict. Many brands started developing discipline-specific bikes and components – the enduro trend was in full swing! Many new locations were added to the event list, and everyone wanted to organise an EWS race in their own backyard, and show the world what great trails they had. The increasing professionalism would inevitably drive up costs, which is something we reported about back in 2015 in this exciting interview with organisers around the world. At the same time, the race format was adapted over the years to optimise spectator viewing and, above all, broadcasting.

From 2018 onwards, there were also countless qualifying events around the world to enable riders to qualify for an EWS spot. Starting in 2019, non-professional riders could enter two separate side events, the EWS 100 and EWS 80, which allowed them to race either the same or a shortened version of the EWS tracks on the same weekend as the pros – a unique experience to enjoy the vibes of the EWS and an opportunity to qualify for a starting place with the pros. Some of these events were fully booked within minutes and getting a race place was like winning the lottery. But of course, many races in different classes taking place at the same time also meant a huge amount of extra work for organisers and promoters.

Little by little, the events got shorter, with many two-day races becoming one-day events with the addition of a pro stage that was held the day before. Locations were often the same and even the stages were familiar to some racers, with venues carried over year on year.

With the end of the 2022 season came major change, which was received very positively and optimistically by most racers. The Enduro World Series, as it had existed until then, was no longer just monitored, but officially taken over by the UCI, and renamed the UCI Mountain Bike Enduro World Cup – EDR in short.

Put simply, the regulations now comply with the official guidelines of the Union Cycliste Internationale and, for the first time in the history of enduro racing, an official world championship title and coveted rainbow jersey are at stake. The UCI also added the E-EDR (formerly EWS-E) to the calendar. At the same time, Red Bull sold their long-standing broadcasting rights to Warner Bros. Discovery Sports (WBD) which also holds the broadcasting rights for the FIM (international motorbike association) and promised plenty of coverage through Eurosport, GCN+ and Discovery+. With the restructure came the hope of additional visibility and publicity, even though viewers now had to pay a subscription service for the first time to be able to watch the pro races live. The two core elements – i.e. the organisation and broadcasting – were now in the hands of the UCI and WBD, starting from the 2023 season onwards. As a result, enduro would now fall into the same league as the Downhill and XC World Cup – or, at least that was what we all hoped.

The first UCI Enduro World Cup 2023 – The dawn of a new era, or the beginning of the end?

The first year of the UCI Mountain Bike Enduro World Cup included two events in Australia and five in Europe, all of which were single day races, with the aim of improving media coverage. Many riders, including Jack, have welcomed this change, as it was going to benefit the fan community and increase the popularity of the enduro racing format. However, at the turn of the year, UCI tripled the registration fee for racing teams. In return, they were going to bundle a few events with the Downhill and Cross-Country World Cups, so that resources from both the teams and the organisers could be pooled – at least in theory.

The first two races in Maydena and Derby were a solid start, proving the UCI’s good organisation, with great spectator turnout and swiftly edited, highly informative video recaps. After this, Leogang was quite a disappointment, and a sign of things to come. The first joint event with DH and XC clearly showed that enduro was being demoted to a fringe event, with the team pits moved far away from the action, poor communication from the organisers, a race that almost nobody noticed, and stages that were primarily held on bike park tracks.

The last two races in Loudenvielle and Chatel, caused concern and frustration in the enduro pits. Once again, poor communication from the organisers marked the day, including countless plan changes and a controversial lack of track marshals and taping, which cost racers like Jack Moir valuable points – and potentially even the podium that day. Furthermore, the jumps on the stages were taped off to make the stages rideable for everyone, which can be extremely dangerous at the warp speed of pros, making you wonder why such things are even taken into consideration during a professional series, especially given that we’re talking about an enduro race with moderate jumps – it’s not exactly the FEST series.

At the end of the season, the bad news started rolling in. Manufacturers like IBIS, Devinci, GT and Polygon pulled out from supporting enduro Factory teams and, if the rumours are true, many more teams and riders will be affected in the near future. Perhaps it’s no coincidence that riders like Richie Rude and Adrian Daily decided to compete in the DH World Cup and try out new – or familiar – disciplines? That being said, it’s also true that teams make such decisions well ahead of time and that negotiations are often underway at the start of the season. Nevertheless, Robin Wallner, team manager of the former IBIS Factory Team, also confirmed to us that the events of last season and countless rumours make the decision more plausible in retrospect, even if for many it means the end of an era.

Grass-roots enduro racing booms, but the pro series is a problem?

Most enduro races around the world sell out within minutes, clearly showing that enduro is alive and kicking. When taking part in a race, not only do you get plenty of riding time with long stages, but also the chance to experience unforgettable moments with your riding buddies, which is perhaps the most important reason for taking part in a race for most amateur racers. On top of that, most of us own bikes that are perfectly suitable for enduro racing straight out of the box, without requiring any major upgrades.

Amazing trails and great vibes encourage people to race enduro, which is why the amateur sport is booming like never before. – Jerome Clementz

Everyone knows, rides and loves enduro and most bike brands have an enduro-specific bike model in their portfolio. It’s the discipline that has aroused interest in the sport for many new riders, and introduced them to riding and racing bikes. Nevertheless, the latest sales figures show a massive trend towards assisted bikes, with eMTB sales surpassing sales figures for analogue bikes by almost 9 times in Germany alone – the trend couldn’t be clearer. This also explains why the bike industry is increasingly interested in eMTB racing, and why analogue enduro racing is the first one to suffer from budget cuts, as we’re currently experiencing. This is mainly down to the fact that the trade is facing a massive wave of insolvencies caused by industry-wide liquidity problems, which can be traced back to overstocking – the aftermath of overzealous manufacturing during the Corona bike boom. From the bike companies’ perspective, you have to ask yourself how much money you can and want to invest in enduro and, above all, professional enduro racing. After all, the sport has established itself, and when money gets tight, the question quickly arises as to what impact a race series like the EDR still has, and whether an investment will pay off in the long term.

It goes without saying that a professional race series like the UCI Mountain Bike Enduro World Cup costs a lot of money. But where does the cash come from and is the investment even worth it, both for the organisers and the sponsors? On one hand, nobody likes to throw money down the drain, but on the other, aspects such as brand identity don’t come with a set price or measurable value.

Team sponsors and bike manufacturers face major costs, as it’s not just the registration fees that have increased. Since our sport is becoming more professional, teams are getting bigger and bigger. Where in the past stood a small gazebo next to a van, with one team mechanic working their magic for several riders at once, now stands a massive team pit with physiotherapists, chefs, in-house photographers and filmmakers, as well as other personnel available to provide the best possible support for the riders on a weekend. And while in the past, the teams’ main focus was on winning races, now they also have to work on their image to ensure maximum visibility for their sponsors to strengthen the brand and market their products.

Local organisers are also struggling with rising costs. Back in 2015, Brandon Ontiveros, the organiser of the EWS round in Crested Butte, broke down some of the costs involved for us, some of which you might not have considered:

“Permits are very expensive and challenging, and shuttles are a huge expense too (300+ riders & over 50 media). Then there is medical support, search & rescue, radio/satellite communication, insurance, legal fees, liquor license, food/catering, equipment rentals, infrastructure and capital equipment needed for the overall event, recycling, marketing, timing systems, charity/non-profit contributions, toilet rentals, course supplies, event vehicles, registration and results services, music/entertainment, number plates/bibs & timing chips, awards/trophies, large pro purse, maps, race booklets, merchandise/apparel, EWS fees and the list goes on.”

Over the years, the increasing professionalism of such events significantly multiplied the costs. This simply puts many organisers off, while at the same time, many locations have neither the manpower nor the space to host an EDR. As a result, small, unknown locations have permanently disappeared from the race calendar, which is exactly what gave the EWS its unique flair.

Exactly where the money from entry fees and the like ends up is pure speculation. The fact is, however, that there’s a huge organisation behind the EDR now, which puts high demands on local promoters and race teams, but didn’t deliver last season. This is especially frustrating given that merged events, such as Leogang and Port du Soleil, should actually help drive costs down. At the end of the day, despite paying more to a bigger organisation, they didn’t get their money’s worth.

Media coverage – and especially the live broadcast – is very likely to be the main source of income for WBD. It is therefore understandable that enduro racing – which hasn’t yet been broadcast live to date – is being pushed into the background, as broadcasting is technically more complex with enduro than with downhill and XC races. Long distances, remote routes and big start lists, with some competitors riding different trails at the same time. Photos and videos shared on social media play a major role in today’s professional sport, and the demands of viewers for high-quality content are huge. This costs a lot of resources and money, especially given that the attention span of today’s viewers is on the short side, meaning that the event loses its relevance after just a few days – but aren’t we all responsible for this after all?

Needless to say, this presents organisers, local promoters, and sponsors with major challenges and requires a great deal of commitment. If a racing series like the EDR is unable to deliver in such unpredictable times, delivering a rather disappointing result after just one season, budget cuts are the quickest, easiest solution – especially considering that the format was cheaper and better in previous years.

Two steps forward, one step back.

The first year is never easy, and even if the last season leaves a lot of room for improvement, we still have at least two EDR seasons ahead of us. Kate Ball, Head of Communications at the UCI Mountain Bike World Series, told us in an email that there are no plans to end the series in 2025. Unfortunately, she didn’t say anything about the following years. The following rather short and diplomatic statement was the only answer we received to our specific questions about the future of EDR, which we asked to understand what would happen after 2025. We also wanted to know where the rumours originated, why the costs rose and how the industry’s current struggles affected the series.

A spokesperson for Warner Bros. Discovery Sports said: “The 2023 UCI Enduro World Cup saw the sport of enduro join the top tier of mountain biking for the first time. Enduro enjoyed extensive TV coverage for the first time in the history of the sport, with Highlights Shows broadcast on Eurosport. In addition, average video views of enduro content on the UCI Mountain Bike World Series YouTube channel were up 132% on 2022.”

“We remain committed to both enduro and e-enduro. The athletes, teams and fans are at the heart of all our decision making as we work to ensure the long-term viability of the sport we love. We listen to all feedback received and look forward to continuing this journey together with the enduro community – including some very exciting announcements to come about the future of the sport.”

Regardless of UCI’s optimistic statement, the 2024 EDR season only includes six European stops, which could be a massive headache for many non-European racers and privateers, significantly reducing their chances of competing in a UCI Mountain Bike Enduro World Cup at all, and reducing global appeal in the process. Although this approach might not seem the most future-oriented, it could be another measure to drive down costs for bike manufacturers in an attempt to help them through hard times.

The bike industry is known for being overzealous at first and then taking a step back to level off. Fortunately, professional enduro racing has had some glorious years and we all know what a good race looks like. But here’s the main question: do we really need an additional series like the EDR Open in the future? Or would it make more sense to run it as a professional series, with simplified logistics and more opportunities, allowing other events to award UCI points? This would give grass roots racing and national racing series more exposure and greater relevance, and hopefully more sponsors – and this also increases the promotion of young talent.

In addition, this year’s Downhill World Cup media coverage, which included live broadcasts of both the preliminary rounds and finals – proved that the audience only has a certain attention span, which doesn’t do justice to the enormous effort and expense put into this year’s coverage. After all, very few people are prepared to spend a whole day watching a race on TV, while on-site spectators are confronted with long waiting times. Simply put, there is no need to broadcast an entire EDR race or a large number of stages live. Furthermore, most of the people we spoke with would love to see a few long, multi-day races again and to get a thorough highlight summary of the events, as well as a tension build-up for the spectators in the finish area. What’s more, the venues are so different that, in our opinion, it makes little sense to resort to a specific format; instead, it would make sense to adapt the number of stages and days to the respective event, as this would put many smaller venues back on the map.

We shouldn’t stick to just one format but adapt each event to the respective venue to get the best out of it. – Sven Martin

Enduro never dies 🤘

There’s one thing we hope everyone will agree on: enduro racing will never die. Even though the current professional series is going through a difficult time, and the future of EDR is still written in the stars (if you believe the rumours), the discipline will live on in its own right. Although we can imagine that some riders would switch to the E-EDR, downhill or even the XC World Cup with a hypothetical end of the analogue EDR, a big majority of them would keep racing analogue enduro bikes. Assuming enduro were to disappear, the competition in downhill, for example, would increase exponentially, resulting in just a small percentage of riders qualifying, and many proven racers not even making it into finals – and thus into the valuable broadcast time.

We’re sure that, sooner or later, the supposed death of the EDR would result in a new professional enduro series – or several. Because there’s plenty of enduro races out there, and lots of enthusiastic, committed people. What we need is an attractive racing series that brings visibility, an established field of riders and the highest possible prize money for world-class racers. What feels like a utopian vision right now, will be achievable in the future, because what’s happening to the bike industry now is just temporary. Incidentally, we are experiencing a similar development with competing series in Supercross and golf, and the same happens in many other major sports.

So maybe in a few years time, we’ll be sitting somewhere in the middle of fu***ng nowhere after finishing one of the best enduro races of our lives. In typical enduro fashion, we’ll be sipping on some cold beer, remembering the dark days of professional enduro racing, and reflecting on how it has evolved and improved over the years – no matter whether it’s a welcome new start or one of us is wearing the rainbow jersey.

And what about eMTB racing?

Aside from the rumours that suggest that there will only be the E-EDR in the future, there are still some unanswered questions about eMTB racing. With eMTB sales surpassing sales figures for analogue bikes, the trend towards electricity is clear, which also points to the direction the bike industry is heading in. However, if you look at the numbers – and especially at your average eMTB buyer – it becomes clear that the eMTBs appeal to an older, less performance-oriented crowd. Furthermore, the way we ride eMTBs doesn’t have much in common with the sport of enduro. Most eMTBs are only used for light trail riding and tours with long paved sections, with only very few users riding their eMTB on demanding trails and in bike parks. As a logical consequence, it seems sensible to assume that the average eMTB buyer isn’t as interested in racing as your typical EDR enthusiast, because mountain biking has a completely different meaning for each of them. Sure, there are also a few enduro fanatics and racers who are interested in eMTB racing, but is it more profitable than enduro racing? Not that we don’t celebrate e-mountainbikes, but what’s wrong with just riding these things for fun?

On the other hand, product development can benefit greatly from the data acquired under extreme conditions, for example while racing. In other words: bike manufacturers can gain a deep technical insight into their products through a factory team, which allows them to further improve components like the motors and batteries, and find ways to make them more durable. This, in turn, strengthens the brand’s image and provides marketing departments with valuable material for content. Moreover, the direct support of bike and motor manufacturers brings factory teams a huge advantage in racing, meaning that privateers would inevitably feel as if they were racing the MotoGP with a scooter. Competitive equality is extremely hard to achieve, with mid-race software tweaks and over-the-air updates being quite common in e-MTB racing. And then there are special high-flow batteries that deliver their power to the motor much quicker, and even batteries with higher-quality cells. To ensure a fair competition, we need comprehensive and detailed guidelines, especially since the choice of motor alone has a serious impact on performance and a powerful, efficient drive system offers a lot of advantages depending on the route and format – as is the case with most motorsport races.

As you can see, there’s still a lot of work to be done. Many of the current eMTB racing formats are sub-standard and criticised by many of the participants. This also applies to the E-EDR, which largely relies on the EDR tracks and complements them with a few uphill stages. Most of the time, these are either unrideable or very unnatural, and only have a minimal influence on the overall race time. At the end of the day, you’re just riding enduro stages with an eMTB most of the time. Depending on the route and format, however, the rider’s weight has a massive impact too: more weight means less propulsion and more energy consumption, meaning that smaller, lighter riders have a clear advantage. To push the sport, we need an eMTB-specific racing format, with specially designed courses and technical regulations – which are all long overdue. That’s particularly important considering that eMTB racing is still seen by many riders as the last stage before retirement. But we already know that phenomenon…

Conclusions

Bad timing or misjudged development? Many aspects have led to the precarious situation professional enduro currently finds itself in, and there’s a lot of uncertainty hanging over our segment. Professionals are worried about their jobs, the industry is worried about its money and professional enduro racing is worried about its vibe. Enduro continues to boom, and none of us want the EDR to end – quite the opposite – but sometimes you just need to take a step back to move forward.

Did you enjoy this article? If so, we would be stoked if you decide to support us with a monthly contribution. By becoming a supporter of ENDURO, you will help secure a sustainable future for high-quality mountain bike journalism. Click here to learn more.

Words: Peter Walker Photos: Sven Martin, Kike Abelleira, Rick Schubert